|

| Baccio Bandinelli The Three Forms of Time ca. 1550 drawing Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York |

" ... in a drawing by Baccio Bandinelli, now in the Metropolitan Museum, the central head even seems to be a self-portrait; where the head standing for the future belongs to a handsome but inexperienced youth, and that personifying the past suggests a Roman emperor as well as an ideal type frequently found in Leonardo's drawings and, according to some, reflecting Leonardo's own features. Bandinelli, in his proverbial arrogance, thus seems to declare his superiority over his successors as well as his forerunners, including even the masters of ancient Greece and Rome, and claiming thereby the place universally allotted to his great rival, Michelangelo. ... In the Life of Bandinelli Vasari characterizes him as a major master and an excellent draftsman but adds that his virtues might be more keenly appreciated after his death than in his lifetime: he had made himself so objectionable by his discourteous manner, his litigiousness and his irrepressible habit of minimizing the merits of other artists that the hostility to his person prevented the just evaluation of his artistic achievement."

– from the lecture Reflections on Time, one of the texts from Erwin Panofsky's Wrightsman Lectures at the Metropolitan Museum. These were published as Problems in Titian, Mostly Iconographic by New York University Press in 1969.

|

| Baccio Bandinelli Portrait of Michelangelo 1522 oil on panel Louvre |

The sculptor Bartolommeo (Baccio) Bandinelli, born in 1493, belonged to the Florentine generation immediately following that of Michelangelo. Though twenty years older, Michelangelo outlived Bandinelli by four years, thus overshadowing his entire life. Bandinelli's perpetual irritation with existence can persuasively be read as an extended response to Michelangelo's dominance. Below, a range of Baccio Bandinelli's carved marbles, the majority still in Florence.

|

| Baccio Bandinelli Self-portrait ca. 1550 marble relief Musée des Beaux Arts de Strasbourg |

| Baccio Bandinelli Self-portrait 1556 marble relief Duomo, Florence |

|

| attributed to Baccio Bandinelli Colossal head ca. 1560 marble Los Angeles County Museum of Art |

|

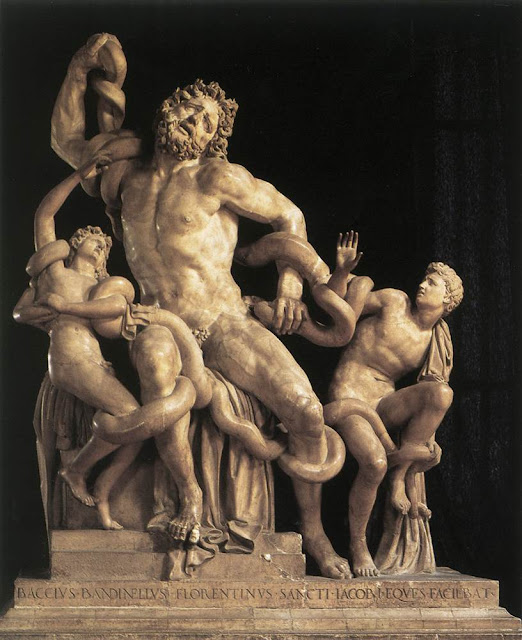

| Baccio Bandinelli full-size copy of The Laocoön 1515-25 marble Galleria degli Uffizi, Florence |

"There had recently returned from France Cardinal Bernardo Divizio of Bibbiena, who, perceiving that King Francis possessed not a single work in marble, whether ancient or modern, although he much delighted in such things, had promised his Majesty that he would prevail on the Pope to send him some beautiful work. After this Cardinal there came to the Pope two Ambassadors from King Francis, and they, having seen the statues of the Belvedere, lavished all the praises at their command on the Laocoon. Cardinals de' Medici and Bibbiena, who were with them, asked them whether the King would be glad to have a work of that kind; and they answered that it would be too great a gift. Then the Cardinal said to them: 'There shall be sent to his Majesty either this one or one so like it that there shall be no difference.' And, having resolved to have another made in imitation of it, he remembered Baccio, whom he sent for and asked whether he had the courage to make a Laocoon equal to the original. Baccio answered that he was confident that he could make one not merely equal to it, but even surpassing it in perfection. The Cardinal then resolved that the work should be begun, and Baccio, while waiting for the marble to come, made one in wax, which was much extolled, and also executed a cartoon in lead-white and charcoal of the same size as the one in marble. After the marble had come and Baccio had caused an enclosure with a roof for working in to be erected for himself in the Belvedere, he made a beginning with one of the boys of the Laocoon, the large one, and executed this in such a manner that the Pope and all those who were good judges were satisfied, because between his work and the ancient there was scarcely any difference to be seen. But after setting his hand to the other boy and to the statue of the father, which is in the middle, he had not gone far when the Pope died."

|

| Jan de Bisschop after a drawing by Baccio Bandinelli Laocoon son ca. 1675 etching British Museum |

"Adrian VI being then elected, he [Baccio] returned with the Cardinal [de' Medici] to Florence, where he occupied himself with his studies in design. After the death of Adrian and the election of Clement VII, Baccio went post-haste to Rome in order to be in time for his coronation, for which he made statues and scenes in half-relief by order of his Holiness. Then, having been provided by the Pope with rooms and an allowance, he returned to his Laocoon, a work which was executed by him in the space of two years with the greatest excellence that he ever achieved. He also restored the right arm of the ancient Laocoon, which had been broken off and never found, and Baccio made one of the full size in wax, which so resembled the ancient work in the muscles , in force, and in manner, and harmonized with it so well, that it showed how Baccio understood his art; and this model served him as a pattern for making the whole arm of his own Laocoon. This work seemed to his Holiness to be so good, that he changed his mind and resolved to send other ancient statues to the King, and this one to Florence; and to Cardinal Silvio Passerino of Cortona, his Legate in Florence, who was then governing the city, he sent orders that he should place the Laocoon at the head of the second court in the Palace of the Medici. This was in the year 1525. This work brought great fame to Baccio ..."

– from Giorgio Vasari's Lives of the Painters, Sulptors and Architects, first published in 1550, translated into English by Gaston du C. de Vere in 1912

|

| Baccio Bandinelli Apollo ca. 1550 marble Boboli Gardens, Florence |

|

| Baccio Bandinelli Orpheus ca. 1519 marble Palazzo Medici-Riccardi, Florence |

|

| Baccioi Bandinelli Prophets 1550s marble reliefs Duomo, Florence |

|

| Baccio Bandinelli Lovers 16th century marble relief Palazzo Bartolini-Salimbeni, Florence |

|

| Baccio Bandinelli Adam and Eve 16th century marble Museo Nazionale del Bargello, Florence |

|

| Baccio Bandinelli Pietà ca. 1554-59 marble Santissima Annunziata, Florence |

|

| Baccio Bandinelli Hercules and Cacus 1525-34 marble Piazza della Signoria, Florence |

"Michelangelo's absence from Florence may have had the most significant impact on the city's sculpture, since it was on sculptural projects that he had mostly been engaged. Among the first public monuments to go up under Duke Alessandro was Baccio Bandinelli's Hercules and Cacus. It was Clement VII who had initially conceived the work, and Bandinelli had begun work on it as early as 1525, but when the Medici fled the city two years later, he joined them. The block at that point went to Michelangelo, who reconceived the composition as a Samson Slaying Two Philistines. When the Medici returned to the city in 1530, they brought Bandinelli with them; he regained control of the marble, and returned to his earlier plan. The final pair, completed the year Michelangelo left town, showed Cacus – an evil giant and cattle thief – enslaved by the semi-divine muscleman. It was placed to the right of the entrance to Florence's city hall, and thus became a permanent pendant to Michelangelo's David. The patron's intention, no doubt, was to neutralize the David's republican associations; the earlier statue was famous enough that it could not simply be moved or destroyed, but perhaps company would dilute its message. Bandinelli himself, put in the awkward position of distracting the attention of a hostile audience from Michelangelo's icon, did what he could to imitate his predecessor, giving his figure a similar scowl and trying to show that he too had studied human anatomy. Vasari writes that, once the statue was in place, Bandinelli even went back and retouched it, giving the figure's physique yet more definition. The comparison with Michelangelo could not favor him, though, and contemporaries responded with scorn. Some attached poems to the work itself, disparaging Bandinelli, his marble, and by implication, his patron. Later, his rival Benvenuto Cellini would rehearse all the criticisms leveled at the time: if Hercules's hair were removed, viewers commented, there would not be enough head left to contain a brain; the muscles seem to have been studied not after a man but a sack of melons; the whole statue seems to be keeling forward."

– from A New History of Italian Renaissance Art by Stephen J. Campbell and Michael W. Cole (Thames & Hudson, 2012)

| Baccio Bandinelli Hercules and Cacus - Lion Head detail 1525-34 marble Piazza della Signoria, Florence |

|

| Baccio Bandinelli Hercules and Cacus - Boar Head detail 1525-34 marble Piazza della Signoria, Florence |

|

| Baccio Bandinelli God the Father War Monument installed 1915-18 marble Santa Croce, Florence |

|

| Baccio Bandinelli Sleeping Hercules 1550s marble Hermitage, Saint Petersburg |